September 23, 2023

Spivey Hall, Clayton State University

Morrow, GA – USA

“Rachmaninoff Reflections”

Inon Barnatan, piano.

Franz SCHUBERT: Six moments musicaux, D. 780 (op. 94)

Sergei RACHMANINOFF: Six moments musicaux, op. 16

J.S. BACH/arr. Sergei Rachmaninoff: Prelude, Gavotte and Gigue from Violin Partita No. 3 in E Major, BWV 1006

Sergei RACHMANINOFF/arr. Inon Baranatan: Symphonic Dances, op. 45

Mark Gresham | 28 SEP 2023

Eighty years ago, on February 17, 1943, the legendary Russian-American composer Sergei Rachmaninoff performed his final solo piano recital in a university gymnasium that doubled as an auditorium at the University of Tennessee in Knoxville.

Rachmaninoff was on a concert tour that had begun on October 12, 1942. He had already decided it would be his final one but had not yet learned until mid-tour that his declining physical condition was due to aggressive cancer. It was also mid-tour, on February 1, that he and his wife Natalia became naturalized American citizens.

Heavy rail was the primary mode of cross-continental travel in the mid-20th century. After the Knoxville concert, the Rachmaninoffs were headed south. By the time the train reached Atlanta, they decided that Sergei was too ill to continue. They changed trains in Atlanta and returned to their home in Beverly Hills, California, where Rachmaninoff passed away on March 28, four days short of his 70th birthday.

Like many of his predecessors, Rachmaninoff’s legacy as a pianist is inseparable from his legacy as a composer—an aspect of the profession that seemed to dwindle post-World War II, as many composers increasingly became “specialists,” aloof from the practicalities of being grounded in a professional performing career (except, perhaps, as conductors).

Although written mainly in the 20th century, Rachmaninoff’s compositions remain primarily steeped in the 19th-century Romantic lineage, particularly that of Tchaikovsky, despite writing in an era of rapid aesthetic change and experimentation.

Despite that, one can still hear some early modern influences (at least one passage from his Variations on a Theme of Paganini sounds almost like a Hollywood big band) and can quickly note his emulation of composers whose works he performed as a pianist (for example, Johannes Brahms’ Variations on a Theme of Paganini, Op. 35, makes use of the same theme Rachmaninoff did in his), influences on Rachmaninoff that went back at least as far as Johann Sebastian Bach—several movements of whose English Suite No. 2 in A minor, BWV 807, opened the aforementioned final recital in Knoxville.

Understanding that historical context lends powerful illumination to the insightful programming choices behind the solo recital by celebrated pianist Inon Barnatan this past Sunday afternoon, inaugurating Spivey Hall’s 2023-24 concert season.

Entitled “Rachmaninoff Reflections,” the program’s first half featured a comparison between two sets of six short works with identical titles: Franz Schubert’s Moments musicaux, D. 780 (op. 94), followed by Rachmaninoff’s Moments musicaux, op. 16.

The pairing of Schubert with Rachmaninoff may at first seem odd (as one other audience member noted) until you recognize that pairing pieces with a form or title in common is a programming asset, in particular for a composer who is active as a performer, as was the case with Rachmaninoff. Again, using his final Knoxville recital as an example, Rachmaninoff, in the second half, programmed pairs of Etudes written by himself, Chopin, and Liszt, with a couple of piano transcriptions of Wagner tunes thrown into the mix, one of them by Liszt.

Schubert’s Six moments musicaux and his two sets of four Impromptus (op. 90 and 142) are among his most frequently played piano music, especially No. 3 in F minor, composed as they were to meet the demands of the Viennese public for “musical album leaves” with amateur pianists of modestly advanced technical skill in mind, yet remain delightfully melodic works for concert performance by top pros like Barnatan.

Rachmaninoff’s Six moments musicaux was composed in late 1896 (although he revised No. 2 in 1940), and each of them hearkens back to characteristic musical forms of the Romantic past. Unlike Shubert’s, their grand style and pianistic challenges make them more suited to the concert stage than domestic amateur music-making. And yet they also contain a certain charm amid their deeply felt expressiveness, revealed well by Barnatan’s performance.

The two sets actually work quite well in tandem.

It’s hardly the first time music from Bach’s Violin Partita No. 3 had been arranged for other instruments, nor the first time his solo violin music had been transcribed for piano. By the time of Rachmaninoff’s arrangement, this had become quite common.

Bach himself transcribed the entire Partita for another instrument (in 1900, music critic Wilhelm Tappert asserted that the arrangement was for a solo lute, but Bach’s manuscript does not specify; it could as easily have been for a keyboard). Further, Bach also re-used and rearranged the “Preludio” as a “Sinfonia” in two later cantatas: for opening the second part of his 1729 cantata “Herr Gott, Beherrscher aller Dinge,” BWV 120a, and more famously the joyous opening sinfonia of the 1731 cantata “Wir danken dir, Gott, wir danken dir,” BWV 29, scored for obbligato organ, oboes, trumpets, and strings.

In the 19th century, due to a renewed interest in the “rediscovered” music of J.S. Bach, arrangements for violin and piano were made from the Partita No. 3 (in whole or in part) by no less than Robert Schumann and Camille Saint-Saëns as well as Fritz Kreisler in the early 20th century.

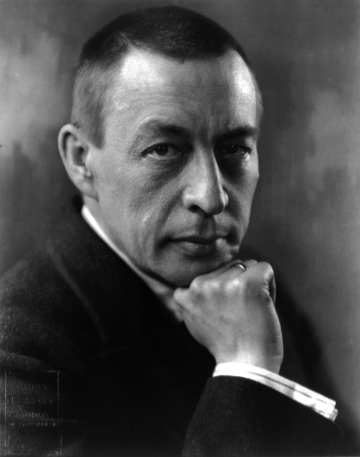

Sergei Rachmaninoff in 1921. (credit: Kubey-Rembrandt Studios, Philadelphia, PA – public domain)

Also, Rachmaninoff was not the first to arrange movements from it for solo piano: Joachim Raff (1868), Rafael Joseffy (1882), and Erkki Melartin (ca. 1919) are among the now minor names whose transcriptions preceded that of Rachmaninoff, though examination of the scores shows Rachmaninoff’s to be demonstrably superior and more intriguing, including the supple hand-crossings observed in Barnatan’s engaging performance, provoking this reviewer to track down the printed score.

Turnabout being fair play, Barnatan then followed with his own solo piano arrangement of Rachmaninoff’s Symphonic Dances, op. 45. The three-movement orchestral suite, completed in October 1940, was his final major composition and the only piece Rachmaninoff wrote in its entirety while living in the United States.

Barnatan’s solo piano version cannot reproduce the Romantic lushness achievable by a large orchestra. Hence, his transcription uses the idiomatic percussive characteristics of the grand piano to greatest advantage, as evidenced in Sunday’s performance, creating an entirely different interpretive approach to the work (Rachmaninoff’s own two-piano version notwithstanding).

All in all, Barnatan’s recital celebrated an almost-lost art of programming and performance familiar to the great pianists of the past, where technical acumen, expressive depth, and insightfully re-creative repertoire merged well on the concert stage. We look forward to future explorations of this type from him. ■

EXTERNAL LINKS:

- Inon Barnatan: inonbarnatan.com

- Spivey Hall: spiveyhall.org

Read more by Mark Gresham.

.png)