October 28, 2023

Cobb Energy Performing Arts Centre

Atlanta, Georgia – USA

Michael SHAPIRO: Frankenstein—The Movie Opera

Atlanta Opera Orchestra, Michael Shapiro, conductor. Singers: Amanda Sheriff†, soprano; Aubrey Odle†, contralto; Kameron Lopreore†, tenor; Andrew Gilstrap, baritone; Jason Zacher†, bass-baritone. (†Glynn Studio Artists.) Gregory Boyle, staging supervisor; Rolando Salazar, assistant conductor; Elena Kholodova, musical preparation; Cason Gilmore, stage manager. Film director: James Whale. Film producer: Carl Laemmle. Universal Pictures (1931). Based on the novel Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus by Mary Shelley (1818). Starring: Colin Clive (Dr. Henry Frankenstein), Mae Clarke (Elizabeth), John Boles (Victor Moritz), Boris Karloff (The Monster), Dwight Frye (Fritz).

October 29, 2023

Spivey Hall

Morrow, Georgia – USA

The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923)

Joshua Stafford, organ. Film director: Wallace Worsley; Film producer: Carl Laemmle. Universal Pictures (1923). Based on the novel The Hunchback of Notre Dame by Victor Hugo. Starring: Lon Chaney (Quasimodo), Patsy Ruth Miller (Esmeralda), Norman Kerry (Phoebus de Chateaupers)

Mark Gresham | 1 NOV 2023

The first day of November was the end of harvest and the beginning of winter in ancient Gaelic culture, marked by a festival holiday known as Samhain. Celebrations began at sundown the previous evening (as the Celtic day began at sunset), with the belief that it was a liminal time when the threshold between this world and the spirit world thinned, making it more likely to have contact with the aos sí (faeries) and the souls of the dead.

By the 9th century, Christian churches in the British Isles began to hold their commemoration of all saints on November 1, a practice Pope Gregory IV then extended to the whole Catholic Church. The day continues to be celebrated by Roman Catholics and many Protestant churches as All Saints’ Day or All Hallows’ Day.

But even though the Christian observance eclipsed Samhain, the Celtic cultural practices did not entirely disappear. Migrants from Celtic cultures in the British Isles and Normandy brought their folklore with them to the United States during the 18th and 19th centuries, and October 31, All Hallows’ Eve, or Halloween, has evolved in our modern times as a celebration of horror, the macabre and the supernatural. Guising as magical or frightening creatures or as characters from a story on Halloween and visiting homes to ask for sweets (“trick or treat”) became a part of American popular culture, not surprisingly parallel to the rising popularity of Gothic literature, both romance and horror. With the advent of motion pictures, likewise movies with a Gothic theme.

In advance of Halloween this year, two significant performing arts institutions in Atlanta presented classic “Gothic” films from the early 20th century with live musical treatments:

On October 28, The Atlanta Opera presented the 1931 Gothic horror film Frankenstein, starring Boris Karloff and directed by James Whale, based on the Mary Shelley novel of 1818, at Cobb Energy Performing Arts Centre in the production Frankenstein-The Movie Opera featuring a score by conmposer Michael Shapiro, who also conducted the performance by The Atlanta Opera Orchestra and five solo singers, four of them from the company’s Glynn Studio Artists.

Then the following evening, October 29, Spivey Hall presented the 1923 Gothic romance, The Hunchback of Notre Dame, starring Lon Chaney, underscored with live music by organist Joshua Stafford.

“Frankenstein” (1931), vintage theatrical poster

“The Hunchback of Notre Dame” (1923) vintage theatrical poster

“Gothic” is a pejorative term, for sure. Gothic architecture is a building construction style common in Europe between the 12th and 16th centuries that originated in France. Design elements that define it include the pointed ogival arches, stained glass windows, high ceilings, and tall, thin columns. (It has nothing to do with the actual Goths, the Germanic and Teutonic tribes of the 3rd to 5th centuries, nor the eponymous fashion movement that emerged in 1983.) In this sense, “Gothic” was used beginning in the 1640s, applied scornfully by Italian Renaissance architects.

This use of “Gothic” was extended by the early 19th century to a literary style characterized by an aesthetic of fear, supernatural phenomena, and the haunting of the present by the past. In writing and later in films, stories portrayed strange things happening in frightening places, typically physical reminders of the past, often through abandoned or ruined buildings, which evidenced a previously thriving society that is presently viewed as in decay. Especially in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, northern European medieval settings were characteristic, including old castles, cemeteries, crypts, and religious buildings suggesting horror and mystery (such as Gothic cathedrals, hence the evolving etymology).

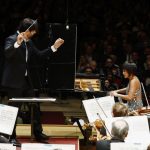

Michael Shapiro conducts his “Frankenstein—The Movie Opera” at The Atlanta Opera, October 28, 2023. (credit: Raftermen)

The idea of turning James Whale’s classic Frankenstein film into an “opera” is an intriguing one, but it posed some hurdles for Michael Shapiro. The film already had spoken dialogue, although absent a musical score. In 1931, the problem of recording the soundtrack onto the film alongside the dialogue remained an unsolved technical problem. That capability would finally come in 1933 with King Kong.

Shapiro had already created three versions of an orchestral score (for large orchestra, chamber orchestra, and wind ensemble) before tackling the idea of creating an “opera” version for the Los Angeles Opera.

With an existing dialogue, as opposed to a silent film, what do you do for a libretto? Shapiro decided to go against directly mimicking or paralleling the English dialogue of the screenplay, which could make the resulting score campy. Instead, he drew texts from the Latin Requiem Mass of the Roman Catholic Church. He found enough relatable sentiment within those texts to underscore the drama in the film successfully.

But is Frankenstein-The Movie Opera actually “opera”? As demonstrated in the Atlanta Opera’s performance, the music is “operatic” in character but does not strike me as being “an opera” per se at all. One of the problems is the sung Requiem Mass text itself. You have to wonder: How many average people in the audience are familiar enough with the Latin text of the Requiem Mass and its meanings to grasp the connections between the liturgy and the Gothic drama taking place on screen? Especially as there were no supertitles or translations projected for these texts, while the English dialogue, which was already dominant, was also included on the screen in subtitles, greatly emphasizing it. what dominated even more was the massive projection of the movie, which filled the opening of the proscenium arch. (Think of the similar impressive size of movie screens in the grand early 20th-century movie palaces, like the historic 4,665-seat Fox Theatre in Atlanta, built in 1929, which surely exhibited the movie when it was first released.)

Even if the audience could not decipher the sung texts (as if the singers were singing wordless voice parts), Shapiro’s music and its performance that evening by the Atlanta Opera Orchestra and singers still effectively underscored the film’s drama and visual atmosphere as it should. And in that, the entire was quite effective, whether an “opera” or not.

Spivey Hall’s presentation of The Hunchback of Notre Dame the following afternoon was a much more humble and traditional affair.

Organist Joshua Stafford (credit Niels Van Niekerk)

A silent film with intertitles, it received a classic musical treatment with the hall’s Ruffatti pipe organ played by organist Joshua Stafford, noted for both his skill at improvisation and for accompanying film.

While the John A. Williams Theatre at Cobb Energy Centre has a capacity of 2,750 seats (therefore balconies and a considerable-sized proscenium), Spivey Hall, on the opposite side of Atlanta, is an intimate recital space with a seating capacity of 492.

One can’t help but wonder how different the experience of The Hunchback of Notre Dame might have been in the Fox Theatre with Stafford playing its four-manual, 42-rank “Mighty Mo” Möller theater organ. But we did have Spivey Hall’s visual centerpiece, the Albert Schweitzer Memorial Organ, a three-manual, 79-rank Ruffatti, accompanying the film. (One also wonders at this late date if Stafford had thought to try to emulate registration available on the Great Organ at Notre Dame de Paris, but the thought only occurred several days after the performance was over, so we failed to ask.) Stafford kept the music underscoring the film well-attuned to the drama on screen.

The only downside to the presentation was that although Spivey Hall is small, the visual element could have benefitted significantly from a larger projection of the film, which did not take advantage of the potential space relative to free-standing screen size or the overall size of the stage. Much of this is surely a matter of projection equipment at hand and the throw of available lenses.

Lon Chaney as Quasimodo in “The Hunchback of Notre Dame” (1923)

Since Spivey is designed as a recital hall (with impeccable acoustics), not a theater (which would have been an acoustical detriment), there are no flies from which to hang a massive roll-down screen. But as venues do become more “media savvy,” one suspects a superior solution for a free-standing screen is available somewhere, perhaps from the technology emerging from traveling commercial exhibits, which could be set up onstage and dismantled with ease.

Both the Atlanta Opera and Spivey Hall shows celebrated the soon-to-arrive Halloween with a festive holiday atmosphere, including staff and attendees in costume and holiday décor. Spivey Hall had holiday treats in the downstairs lobby for the audience. The Atlanta Opera had a massive after-show party.

In both cases, while these events seemed to draw fewer overall attendees than their typical shows, both presenters also clearly attracted some new and different audiences into their circle. And for any presenter, that’s a good and desirable thing. ■

EXTERNAL LINKS:

- The Atlanta Opera: atlantaopera.org

- Spivey Hall: spiveyhall.org

- Michael Shapiro: michaelshapiro.com

- Joshua Stafford: concertartists.com/artists/joshua-stafford

Read more by Mark Gresham.

.png)