Mark Gresham | 27 FEB 2024

Operatic bass Kevin Burdette returns to The Atlanta Opera stage this weekend as Bottom in a production of Benjamin Britten’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

Burdette has a notable performance history with The Atlanta Opera, beginning with his company debut as The Pirate King in a 2016 production of The Pirates of Penzance. More recently, in the company’s Big Tent Series during the pandemic, he portrayed Death in The Kaiser of Atlantis and Peachum in The Three Penny Opera; post-pandemic, in 2023, he played Dr. Voltaire/Pangloss in Candide.

Elsewhere, he recently portrayed Papinou in the world premiere of The Diving Bell and the Butterfly with The Dallas Opera, and he is soon to reprise what is for him a familiar role, Doctor Bartolo, in Rossini’s The Barber of Seville, with Seattle Opera. He has also sung the title role in Sweeney Todd on several occasions with different companies.

Burdette is widely known and respected as a performer for his comedic sense, both onstage and off. EarRelevant publisher and principal writer Mark Gresham recently spoke with Burdette to discuss comedy in opera. The conversation quickly expanded to what essentially underlies both comedy and drama.

The Q&A below is drawn from that conversation and is edited for length and clarity.

Mark Gresham: Kevin, you are preparing to sing the role of Bottom in The Atlanta Opera’s production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and that particularly intrigues me in terms of comedy because while Bottom is a comic character he touches on some serious topics, such as the blurring of reality in theater, which I guess has a lot to do with comedy itself. So, with that in mind, could you share with us your approach to comedy and opera?

Kevin Burdette: I work with the Atlanta Opera’s Glynn Studio Artists as their drama/acting teacher. I have a whole bunch of foundational quotes that I use with them to mostly inspire them to reveal their story. A lot of young artists confuse originality with being new or being something different from that which has come before, when in fact, originality is being the origin, being the source of the story. I’ve talked a lot about that and I embrace that a lot in my acting, whether it’s dramatic or comedic acting.

Among the onslaught of quotations they get from me is one by Dan Fallon that is “a great artist finds a way to touch others by producing works that resonate with the truth that they feel within themselves.”

So in my heart, I am a goofball, but I also am someone who truly believes in the power of performing, the power of theater to reach across the footlights and resonate with an audience; someone who believes that the vibrations of what I’m doing on stage and especially with singing the literal vocal vibrations are enough that they can fill a room and vibrate in the bodies and the hearts of the audience.

I’m passionate about that and so is Bottom. Bottom believes so strongly in the power of being able to tell a story and move people. And it’s at the end of that play within the play, he is so devoted to this Romeo and Juliet type story, when he dies at the end, like I feel like he’s heartbroken that the Royals have intervened and said, “please, no, don’t die.” He’s so committed to telling this story, and it’s that commitment that is the foundation of the comedy.

It’s a little different from, like, Bartolo in The Barber of Seville.

Another of my quotes, is from Mike Nichols, and he says “when you’re on stage you’re not an actor speaking” or, I guess for me, I’m not an actor singing. It’s what I’m feeling and what I’m thinking. So when Bartolo is singing his “Patter Aria” [“Signorina, un’altra volta”] to Rosina, he’s basically saying, “I’ve got you, you can’t escape again.” But with the help of Rossini, we’re also feeling what he’s thinking and it’s basically a dance, the pattern [sings example]. And that’s what he’s thinking. “I’ve got her. I have someone in my old age that’s gonna be with me forever” and inside, his heart is just a-flutter and he’s dancing. That joy is shown in the staging. That’s when the audience laughs because it’s so real and it’s so almost unexpected from this doting old man. “You can’t leave me. I’m a grumpy old man. Everything is gonna be my way.” I would say Bartolo is basically the antagonist in the show. He’s old age. He’s the past. And all of a sudden he sings [sings example] and that’s just funny.

MG: You used the word “original.” Does the word “authentic” resonate with you?

KB: Oh my goodness. I’m so glad you said that! I am very much devoted to Brené Brown and [her self-help book] Daring Greatly. And what Brene Brown says is, basically, vulnerability and authenticity are the birthplace of creativity and empathy. Those are the foundation of what we do as performers. We have to be creative, we have to be authentic and tell our authentic story. That’s the birthplace of empathy and it’s empathy that gets the audience. The audience is there to empathize with our plight, and to see their stories and our stories. We are the protagonist in our own story. We cannot exist alone, although increasingly as we go further and further behind our computer screens and behind our telephones, we feel like we can exist alone and sort of comment on articles, but as human beings, we have to be out, we have to be part of something bigger. And that is the foundation of why we tell stories. When I go to a theater to watch a play or an opera, I want to see my story being told, I want to feel my story being told. And when I feel that, that is when opera or theater or the human condition is at its best.

MG: All of these things seem to me to not apply just comedy but all of drama and comedy, all types of performing.

KB: Absolutely! That is absolutely true. The root of good drama is also the root of good comedy. My goal is my goal whether or not I’m trying to make you laugh or make you cry, and I’m not trying to do either of those things.

Lenny Foglia, who directed The Diving Bell and the Butterfly, said, “You can’t be an asshole. You can’t play an asshole, you can’t play a jerk. You have to play yourself, you have to play a character.” But what my goal is, and I think it was A.O. Scott from The New York Times who said this: “My job is to show the audience something it didn’t know it needed to see.” Whether that’s why Claggart acts like he does with Billy Budd or (flip to a different Britten, A Midsummer Night’s Dream) the way Bottom acts, my goal is to show the audience something they didn’t know they need to see, or to have the audience remember something they didn’t know they had forgotten, and that could make you laugh or that can make you feel. But you have to have some of that root authenticity. You can’t just play Claggart as a jerk. You have to be Claggart as someone who, when he spits over Billy Budd and says, “I will destroy you,” he realizes that when he does, he will also be destroying himself.

MG: There’s the element of, of a character being both dramatic and comedic at the same time and not being clearly one or the other.

KB: And they should be, because that’s what human beings are.

It’s interesting that with the operas that are more rooted in Commedia dell’arte, I find it more difficult up front to show both sides, if that makes sense, because a performer has to study what the Commedia style is. Which character are you performing? And there are certain gestures that go with that.

I guess, as in all art, you start with the structure of it. You start with the Apollonian. What is the technique? Do I know what it is for a Commedia opera, for a Barber of Seville or Don Pasquale? Or, I suppose, for the play within the play of A Midsummer Nights Dream? What are the poses I strike as a comedic character? What is the foundational sort of technique of what I need? But that has just to be the starting point and then you have to imbue it with the Dionysian, with actually what you are inside, not just the structure of it.

It’s like a house. You have the structure of the house, you have the walls of the house which are invaluable. But it’s what’s in the house that makes it a home, and it’s what’s within the Apollonian. That is what actually resonates with an audience. So even in Commedia show like The Barber of Seville, Bartolo at the end, when he realizes, “wait a minute, these people are smarter, younger, the future is now, and I’m not part of it,” it needs to be heartbreaking. When Don Pasquale gets slapped by Norina, it need not to be funny. There were plenty of people in the audience for whom that will be the most powerful point for them. When Bartolo sits in a chair, removes his wig and listens to Almaviva sing his triumphant Aria, that is almost the point of Bartolo at the end. It makes you laugh and then realize: “Oh wow. Getting old, man, We’re all done.”

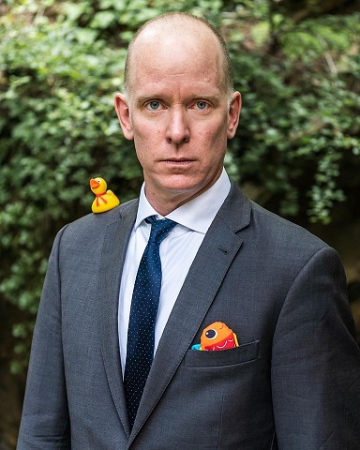

Kevin Burdette in 2016, making his Atlanta Opera debut as The Pirate King in “The PIrates of Penzance.” (courtesy of The Atlanta Opera)

MG: We talk about structure, and I think of the role of improvisation in performance. Maybe that’s the wrong word but or maybe just the most extreme word, but what I mean is dealing with all of the things, either comedic or dramatic, that are not necessarily in either the libretto or the music but are part of stage craft and may be implied by both; the personal insights that you bring through the craft to the opera. You mentioned taking off the wig at the end of The Barber of Seville, for example. How many singers playing Doctor Bartolo take off the wig? Is that part of the libretto or is that staging instructions or is that your own approach? How do you deal with all of those aspects of making the role more authentic and alive by bringing your own creativity into it?

KB: Removing the wig, to my knowledge, is definitely not in the score nor the libretto. You know, we are a part of all that we have met and when you’ve been doing a role for a quarter of a century, you’ve met a lot of people and you take ideas from whatever. In one production that was suggested and it was perfect. And so now, it’s what I feel in my heart. And I don’t I don’t necessarily suggest it to the director of a new production, when I arrive. But if it feels appropriate, I will suggest it.

It’s similar to, in Sweeney Todd, where I think it’s super, super important, if the production will sustain it, for Sweeney at the end to reveal his neck to Toby and basically tells Toby, “I am dead already.” I’m kneeling over my dead wife, who I’ve been obsessing on for the whole show since I escaped prison, coming back to find, to find my Lucy. And I realized that she’s dead in front of me and that I killed her. And I realized now I too too now am dead. I cannot go on from this. What I am, who I am, has been taken out from under me and I am nothing.

So I now reveal my neck to Toby, one of the few really good people in the opera, and I allow him to cut my neck. I think that helps Sweeney’s story. I think that helps Toby’s story because, having seen Sweeney many times, I always feel a little uncomfortable with Toby. All of a sudden, most of the people who are doing the killing are the ones who get their comeuppance, but Toby doesn’t. I don’t see Toby as a straight up killer. And so I think it helps Toby’s story.

I also think it helps the audience feel like the story has come to an end as opposed to just stopped. I had a voice teacher once who told me, when you’re singing, you have to know the difference between ending and stopping, stopping a sound and ending a sound, and you want make sure you end to the sound. Similarly, in Sweeney Todd, I think the audience appreciates it if the story ends rather than just stops.

MG: Did your early life strongly impact your sense of comedy?

KB: I’m the youngest of five children. I was the way I got my or in at any point in a family dinner was by being funny and being fast and funny because if you’re, if I wasn’t, I would not be heard. So it was being funny for me is definitely off stage is definitely part of what feeds how I do comedy on stage.

MG: The late Peter Shickele had a long standing complaint that on the one hand, he had his comedy routine of P.D.Q. Bach, but he was also a serious composer of music, but whenever he wrote a new piece of music, people expected it to be funny. Have you experienced that same kind of thing as singer-actor? Because so many people talk about your abilities at comedy, maybe they don’t take you seriously when you play a totally serious role?

KB: Correct. My buddy Ned Canty who he runs Opera Memphis, he’s a comedy genius. He calls it the “Kramer Effect” – like Kramer from Seinfeld. He says I have an issue I have to overcome both in comedy and not in comedy of the Kramer Effect: I come in a room and people laugh. But in this instance, I’m not trying to make you laugh. I’m literally just walking in the room.

So I have to overcome that. I tend to do it with, like for Sweeney, I am very still at the beginning; a huge stillness which is hard for me because I like to move. I do this thing that I actually learned from Christopher Alton, another director I work a ton with where every physical action, every facial expression, every interesting thing I want to imbue the physicality of a character, I put into an energy in front of my still body, but with the same energy of a truck where you’re holding on the accelerator and the brake at the same time. I am manipulating the energy in front of me to do all the stuff I would do if I were trying to be funny, or trying to move around, but I am just standing there still with the same intention but not moving.

I forget who it was, but someone once said when you stand still on stage, you’re telling the audience what I’m doing now is more important, even in comedy, but especially in drama. If I make an entrance as a bad guy or as a dramatic character, or even as Bottom. Bottom has a long night and a long arch. You have to show his seriousness pretty early on to show how committed he is to telling this story. and that’s when the stakes get set. So for me, stillness is the key for me to making sure people don’t immediately laugh because I’m a goofball and if I move people are like, “Yeah, yeah, yeah, you moved!” Like… no.

Kevin Burdette in a more serious moment. (source: kevinburdette.com)

MG: Any final thoughts to share about your approach to opera?

KB: I have a credo about opera. It comes from Maryanne Wolf, her book Proust and the Squid: The Story and Science of the Reading Brain. She talks about the power of reading, of diving into a book, but I think it’s super applicable to opera; to being in a space where people are performing opera.

She writes: “When we pass over into how a knight thinks, how a heroine behaves, and how an evildoer can regret or deny wrongdoing, we never come back quite the same; sometimes we’re inspired, sometimes saddened, but we are always enriched. Through this exposure we learn both the commonality and the uniqueness of our own thoughts — that we are individuals, but not alone.” And for me, when sitting in an audience listening to something reveling in the vibrations that are coming off the stage and vibrating in me, I say that’s my story, that person is telling my story. And that’s why I’m reveling in my uniqueness, but also my commonality that I am an individual, but here I am and everyone else is resonating with the story too. I’m an individual, but I’m not alone. And for me that is the power of opera. ■

EXTERNAL LINKS:

- Kevin Burdette: kevinburdette.com

- The Atlanta Opera: atlantaopera.org

Read more by Mark Gresham.

RECENT POSTS

Luisi and Dallas Symphony revel in Respighi, Bruce Liu excels in Saint-Saëns’ ‘Egyptian’ Concerto • 13 Oct 2025

Luisi and Dallas Symphony revel in Respighi, Bruce Liu excels in Saint-Saëns’ ‘Egyptian’ Concerto • 13 Oct 2025 Kwamé Ryan and the Charlotte Symphony, with violinist Gil Shaham, deliver a rapturous all-Tchaikovsky evening • 11 Oct 2025

Kwamé Ryan and the Charlotte Symphony, with violinist Gil Shaham, deliver a rapturous all-Tchaikovsky evening • 11 Oct 2025

.png)