May 10 and 11, 2025

Reynolds Auditorium

Winston-Salem, North Carolina – USA

Winston-Salem Symphony, Michelle Merrill, conductor.

Sarah Kirkland SNIDER: Something for the Dark (2016)

Gustav MAHLER: Symphony No. 1 in D Major (1886–93)

Christopher Hill | 13 MAY 2025

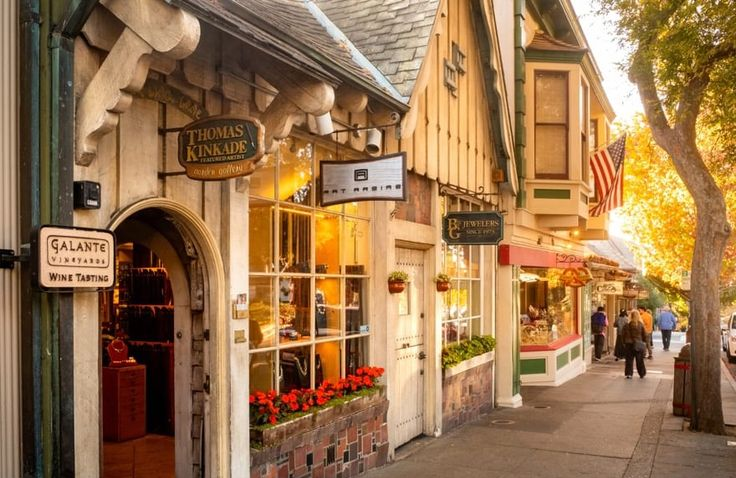

Winston-Salem, the oldest and westernmost node of the North Carolina Triad, was once best known for its strong tobacco and textile economy. Today, those industries are still a presence, but banking, healthcare, education, and manufacturing also contribute importantly to the metro economy, and downtown Winston-Salem reflects this infusion of new commerce. Quite a few blocks of it exude both charm and economic health. This spring weekend, they appeared lively even on a Sunday morning, full of families and foodies in search of a great brunch. Not far from the heart of downtown, The Reynolda House was (and is) showing an impressively curated exhibition of Andrew Wyeth, and in the mid-afternoon, the Winston-Salem Symphony performed its season finale at the Reynolds Auditorium, also convenient to downtown.

Having attended Eastern Music Festival programs conducted by Gerhard Schwarz for several summers in Greensboro, your reviewer should no longer be surprised at the professionalism of classical music performances in the North Carolina Triad. If this is “regional” music making (and I guess it is), “regional” has come a long way during my lifetime. Budgets may be smaller and concerts fewer, but the quality of the performances is indisputable.

Music director Michelle Merrill was assistant to Leonard Slatkin at the Detroit Symphony for several years and is now building her career in the Southeast with the Coastal Symphony of Georgia and the Winston-Salem Symphony. Her program for this weekend’s concerts comprised two works of related emotional content, as she explained in her opening remarks from the podium.

What the music director left as a surprise for the audience was her intention to segue via an attacca from the quiet ending of the first piece to the quiet opening of the second, with only time for a quick breath in between. This made Something for the Dark by Sarah Kirkland Snider more of a prelude to Mahler’s Symphony No.1 than a work with its own artistic identity. In point of fact, the tone poem, inspired by a 1960 poem by Philip Levine, is indeed a work with its own strong profile. Premiered in 2016 by the Detroit Symphony Orchestra, the 12-minute piece was quickly taken up by other U.S. symphonies, including the North Carolina Symphony, which performed it in April 2018. (The Atlanta Symphony Orchestra has performed Snider’s 2020 piece Forward into Light, and the Georgia Tech Orchestra has performed parts of her 2010 song cycle Penelope for mezzo-soprano and chamber orchestra.)

Sarah Kirkland Snider (sarahkirklandsnider.com)

In an uncommonly candid and pithy paragraph, the composer writes, “Initially, I envisioned [the opening musical] motif journeying through a bit of challenge and adversity to arrive at an even stronger, bolder version of itself: Growth! Triumph! A happy ending!” This, of course, is exactly the journey Mahler’s First Symphony takes. It’s not Snider’s journey, though. She continues: “But that wasn’t what happened. Early into its search for glory, the motif finds itself humbled beyond recognition … then put through a series of challenges that roil and churn it like the sea tossing a small boat … Eventually, the music finds its way to solid ground, and though its countenance has now darkened, its heroism a distant memory, there is serenity and some wisdom — and perhaps, even, the kind of hope that endures.” Making Something for the Dark a prelude to the Mahler, then, is equivalent to making hard-fought lessons of middle age a prelude to the untested certainties of youth.

Ms. Snider’s musical idiom is easily approachable on first hearing. Like a number of other current composers who get face time in orchestral concerts today, she samples music from the first half of the 20th century, then deploys these samples in shifting, sometimes dappled, sometimes shimmering layers, sometimes harmoniously, sometimes dissonantly. It was hard for this listener to hear the heroic qualities imputed by the composer to its opening, but that may simply be because this listener is used to music by guys, where heroism is often connected to bringing home meat, an activity that has long called for horns. But getting back to Something… During the roiling and churning part of Snider’s piece, bitonality was most strongly in evidence.

On the other hand, diatonically “stuffed” first- and second-inversion triads (common in Stravinsky, Ravel, and Copland) seem to be associated with solid ground and calmer waters. The composer took advantage of winds in triplets by including lovely paragraphs in which each family has its own identifiable layer. On first hearing, at least, your reviewer believes this composer’s voice to be most evident in her commitment to emotional narrative and in her sampling choices—drawing on soundscapes that please not because they are tonal (they aren’t, mostly) but because they are harmonious. As for the performance, balances could have been more transparent, but on the whole, the orchestra, under Maestra Merrill’s baton, played with convincing engagement and sensitivity.

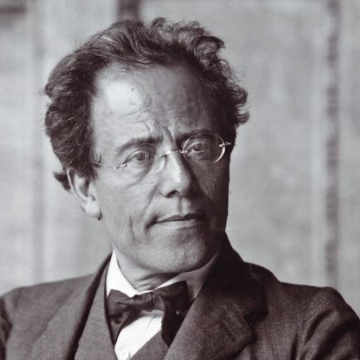

Gustav Mahler (detail of an historical photograph)

Since Universal’s publication of the International Gustav Mahler Society edition of Symphony No. 1 in D Major in 1992, it’s been abundantly clear how much and how often Gustav Mahler tinkered with the score of this work, even into his last years. The third revised edition of the conductor’s score appeared in November 1910, just a month before Mahler conducted the symphony for the last time (with the New York Philharmonic). Even that edition doesn’t capture all of Mahler’s final changes. Today, then, when we listen to live performances of Symphony No. 1, we are hearing both a youthful effort and the most highly polished work in the composer’s canon.

Speaking of youthful effort, it took some time for the symphony to get to a stage where it was ready for polishing. For its first nine years, the work was titled Titan, a Symphonic Poem. And during those years it was very much a work in progress: the version Mahler tried to audition for other conductors (mostly unsuccessfully) in 1886 was different from the version he tried to audition for them (mostly unsuccessfully) in 1887, and so on. In all those versions, however, Titan comprised two parts, the first having three movements, the second having two, but with the final movement lasting substantially longer than any of the other four. The symphony, more or less as we know it today (but before many reworked passages), dates from 1893.

The published score suggests a total performance time of about 54 minutes. For the record, Mahler’s December 1910 performances with the New York Philharmonic were said to be 50 minutes long. (That doesn’t mean the composer would have conducted it the same way in, say, Vienna, Budapest, or Berlin. But it does show, at the very least, that he was open to faster performances.) Chailly and the Royal Cocertgebouw Orchestra take 57 minutes on disc.

There was nothing wishy-washy about Ms. Merrill’s take on the work. Your reviewer did not time the Winston-Salem performance, but it could well have taken longer than 54 minutes simply because this interpretation was characterized by such large and bold gestures, albeit within a general context of balance. Translated: fast sections were brisk (though not rushed), moderate sections (like much of the second movement or the opening of the first movement exposition) were appropriately relaxed, and slow sections (like the first-movement introduction and its returns in the fourth movement) were, well, s-l-o-w. In fact, one audience member was twice seen nodding off during these sections (better that than flashing a bright phone screen). In all movements, portamentos were generously but also tactfully applied, giving the performance a distinctively non-regional feel.

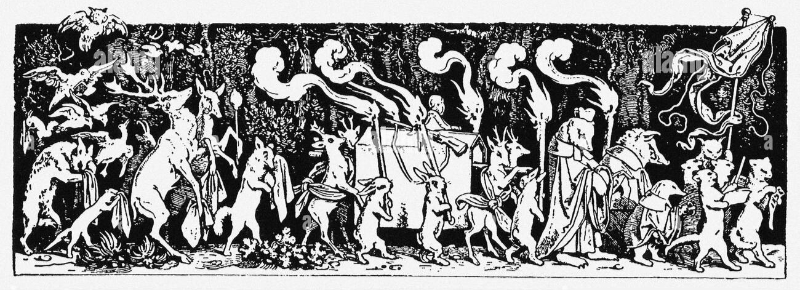

In your reviewer’s opinion, the most striking movement in Winston-Salem was the third, with its juxtaposition of cultural layers. According to Mahler disciple Bruno Walter, the “grotesque” third-movement funeral march was inspired by Roquairol, the introspective, scornful, dangerous antihero of Jean Paul’s 1803 novel, Titan (a title borrowed by Mahler when this symphony was a symphonic poem). It does not contradict Walter to say we also know that in the 1880s Mahler lived for a while with a family whose children often sang the solemn canon “Bruder Martin,” which the third movement builds on. We know, too, that widely disseminated in children’s books of Mahler’s generation was the woodcut “The Hunter’s Funeral Procession” (1850) by Moritz von Schwind in which forest animals carry the bier of a dead hunter.

“The Hunter’s Funeral Procession” by Moritz von Schwind (1850)

In short, Mahler was something of a sampler himself, and he constructed the third movement almost like a collage of different social memories from his early years. That, at least, is how Ms. Merrill seemed to interpret it, aided by great precision in her application of tempos and quicksilver tempo changes, all coordinated for maximum effect. Over five decades of familiarity I can’t think of a performance of this third movement more telling than hers, even if the klezmer passages, though well done, lacked the ultimate degree of ethnic tastiness.

In terms of its proportions and musical arguments, the symphony’s final movement contains much of its meat. The composer once referred to it as “the cry of a wounded heart.” And in an 1888 letter to a friend, Mahler described his current state of depression by saying, “If this goes on, I shall soon cease to be human. I am in the emotional state of the finale of my symphony.” Your reviewer is happy to report that the Winston-Salem Symphony rose to the occasion. In the previous movements there had been two or three minor split notes in the horns, but here in the symphony’s most demanding music it’s not too much to say that the horns played gloriously. One might have been in Chicago back in the Dale Clevenger glory days. The rest of the brass were likewise superbly effective in Mahler’s powerful sforzando-crescendo sectional gestures.

The second subject of the movement is one of Mahler’s best tunes, and here Ms. Merrill used her predilection for bold gestures to excellent effect, not only giving her string section permission to wallow but sculpting their immersive behavior in a way that begs for the German word gemütlichkeit. It’s like syrup, but it’s in no way sentimental. You know it uniquely when you’ve experienced it, just like the unique blend of reserve and warm-heartedness found among cultured Viennese before World War 2. Result: the second theme, too, sounded glorious, both in its initial presentation and in its more troubled recapitulation. Mahler takes care of the symphony ending on his own, thanks to his scoring skills and sincere musicality. In Winston-Salem, the conductor and orchestra followed his directions to the letter and received a sustained ovation for their efforts. I daresay they would have received a similar response in larger venues. These days, “regional” refers more to the number of concerts in a season than to the quality of the concerts.

In sum, this reviewer encourages classical music lovers to enjoy live music-making like this while it’s still possible. In 2025, regional orchestras like the Winston-Salem Symphony are at their highest point of accomplishment ever. But it’s no secret that the level of interest needed to sustain the loftiest forms of European-derived culture will be gone once the Boomers are gone—and they’re going fast. Along with the Boomers will likely go much of the funding for regional symphonies, operas, and the like (despite the best efforts of such organizations to cultivate new audiences). So enjoy this Indian Summer of recreative artistry while it lasts. ■

A street in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. (credit: Christopher Hill)

EXTERNAL LINKS:

- Winston-Salem Symphony: wssymphony.org

- Michelle Merrill: michelle-merrill.com

- Sarah Kirkland Snider: sarahkirklandsnider.com

Read more by Christopher Hill.

RECENT POSTS

The Atlanta Opera conjures a night of enchantment as Glass’ score reawakens Cocteau’s ‘La Belle et la Bête’ • 20 Nov 2025

The Atlanta Opera conjures a night of enchantment as Glass’ score reawakens Cocteau’s ‘La Belle et la Bête’ • 20 Nov 2025 Jan Lisiecki on discipline, performance psychology, and programming for his Spivey Hall recital • 17 Nov 2025

Jan Lisiecki on discipline, performance psychology, and programming for his Spivey Hall recital • 17 Nov 2025

.png)