September 12-14, 2025

Meyerson Symphony Center

Dallas, TX – USA

Dallas Symphony Orchestra, David Robertson, conductor; Emanuel Ax, piano.

Samuel BARBER: Overture to The School for Scandal

Ludwig van BEETHOVEN: Piano Concerto No. 3 in C minor, Op. 37

John Coolidge ADAMS: Harmonielehre (first DSO performance)

Gregory Sullivan Isaacs | 16 SEP 2025

The Dallas Symphony Orchestra opened its 2025-2026 season on Friday evening at the Meyerson Symphony Center with an odd collection of orchestral masterworks from very different eras. Perhaps guest conductor David Robinson had specific connections in mind when selecting this curious collection, but they were not readily apparent (at least to this writer). Musical milestones, maybe?

The concert began with the young Samuel Barber’s first work for a full orchestra, the Overture to The School for Scandal. He wrote it in 1931 while still a student at the newly established Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia. It is brimming with the youthful exuberance that we sometimes discover in exceptionally gifted college students eager to stretch their creative wings.

It is a concert overture and not intended to be attached to the play, a comedy of manors, written in 1777 by Richard Brinsley Sheridan, the infamous rake/poet/playwright/politician/bon-vivant and owner of the London’s Drury Lane Theater.

Robinson launched into Barber’s overture with pizzazz, bringing out the composer’s fragmented musical jumble and sheer youthful energy. The second theme, given to the oboe, was beautifully played, and the upbeat coda brought the performance home.

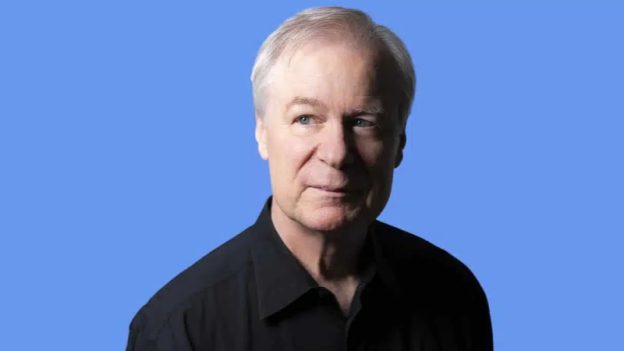

Pianist Emanuel Ax (credit: Lisa Marie Mazzucco)

Beethoven’s majestic Piano Concerto No. 3 in C minor is a fascinating glimpse into Beethoven’s thinking as he began his transition from the more Haydn-dominated classical period into the Romantic style he would come to define. That is immediately evident with the first movement’s dated double exposition contrasted with the gorgeous second movement and boisterous final rondo. Maybe this dichotomy resulted because he started sketching the concerto long before its 1803 premiere, with Beethoven himself at the keyboard. Musicologists are unsure of what he actually played on that occasion because he ran out of time to finish writing out the solo piano part.

We heard this duality in Emanuel Ax’s performance as the soloist. Many pianists try to turn this into a showpiece, but listening to his more refined approach, the concerto took on a completely different feel. He became an equal partner with the orchestra, commenting on the music. In the more sedate second movement, Ax brought warmth to the lyrical theme. But when he got to the final Rondo, he let some fireworks fly, creating an almost amusing back and forth with the orchestra. This was a performance to remember.

The second half of the program presented a performance of John Adams’ 1985 work, Harmonielehre, a sprawling 40-minute piece of minimalism with late romantic era overtones (a DSO premiere). To highlight this unusual partnership, Adams borrowed the title from Arnold Schoenberg, who launched the atonal era, and used the word in his 1911 music theory book.

Harmonielehre is in three large movements, all inspired by bizarre dreams and thoughts.

First, a definition.

Minimalism in music emerged in the 1960s as a revolt against the bleakness of serialism and its extreme practices. These minimalist composers began by rejecting all of that, returning instead to the elegance of a simple C major chord. They took elemental tonal materials and developed them through rhythmic repetitions, juxtaposing them with constantly changing patterns.

Adams cast this work in three movements, and while all are different, the overall impression is one of enormous complexity. However, this is a work that you have to experience in a live performance to understand its power and the immensity of its concept. Robinson brought out its many moods, from the pain of the ever-unhealing “Anfortas Wound” to the lighter finale, graced with the nickname Adams gave to his infant daughter – Quackie.

Performances of Harmonielehre, whatever you may think of it, masterpiece or not, are rare, and getting more so. Just like any work that so defines an era, it is a fool’s errand to project its longevity. But, as a product of the 60s, I am grateful to the DSO for giving all of us the chance to hear what was (or is) such a milestone. ■

EXTERNAL LINKS:

- Dallas Symphony Orchestra: dallassymphony.org

- David Robertson: conductordavidrobertson.com

- Emanuel Ax: emanuelax.com

Read more by Gregory Sullivan Isaacs.

![Composer George Tsz-Kwan Lam and librettist David Davila work with their performance team for the 96-Hour Opera Project 2024. (courtesy of The Atlanta Opera]](https://www.earrelevant.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/ATLOpera_96Hr_BBB0710_800x450-150x150.jpg)

.png)