Mark Gresham | 27 AUG 2025

The new American nation staked its claim to self-determination when the Founders signed the Declaration of Independence in 1776, but its territory remained narrow, pressed between the Atlantic and the Appalachian Mountains.

The Revolutionary War’s conclusion in 1783, sealed by the Treaty of Paris, secured not only independence but also new territory from the British, who relinquished their claims to lands south of Canada and north of Florida all the way to the Mississippi River. It was America’s first step westward.

Two decades later came another leap of far greater scale.

When President Thomas Jefferson signed the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, doubling the size of the United States in a single stroke, he was not only expanding the nation’s territory. He was also acquiring its most cosmopolitan musical city.

A map of the Louisiana Purchase overlaid on a modern map of US states. (Wikimedia/William Morris. Permissions: CC BY-SA 4.0 Link)

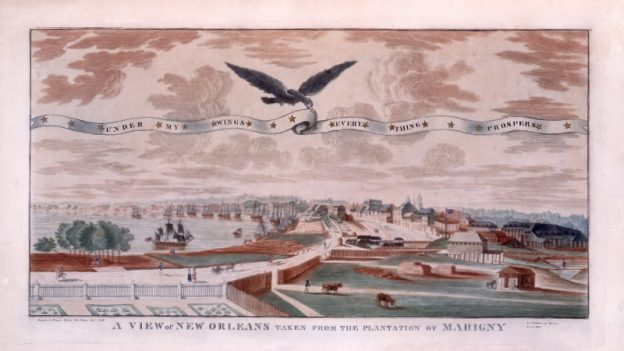

New Orleans, founded by the French in 1718 and ruled by Spain for four decades before briefly returning to French control, entered the Union already carrying a cultural weight that outstripped that of many American cities to the east. By the time Jefferson’s emissaries closed the deal with Napoleon’s negotiators, the Crescent City had an opera house, a cathedral filled with sacred music, salons hosting chamber performances, and Congo Square alive with African rhythms. It was a city where music of many worlds converged — and unlike anything else in the young republic.

Elsewhere in the United States, classical music remained largely an import, thinly rooted, and mostly confined to large cities along the Atlantic seaboard.

Charleston, South Carolina, had the St. Cecilia Society, founded in 1766, one of the earliest concert-giving organizations in America. Its subscription concerts were polished affairs, with symphonies, concertos, and chamber works performed in candlelit ballrooms for the city’s elite planters and merchants — the wealth of whose estates rested on the trading of rice and enslaved labor.

Boston, still shedding its Puritan suspicion of secular entertainment, cautiously developed concert life in the late 18th century, building a taste for Handel oratorios and symphonies.

Philadelphia, the nation’s capital until 1800, was a hub of theaters and music societies. Composer and pianist Alexander Reinagle, who had once studied with Haydn, settled there and presented works by Mozart and his contemporaries to the colonial audiences. Reinagle even composed the funeral march played for George Washington in 1799, underscoring how music was woven into the young nation’s civic rituals.

New York’s theaters staged operas, ballad operas, and concerts, feeding a growing appetite for European entertainment. Yet west of the Appalachians, on the frontier in Kentucky or Tennessee, music was mostly homemade: hymn-singing, fiddle tunes, and traveling performers. A settler could pass a lifetime without hearing a Mozart quartet.

New Orleans was different. Its Théâtre de la Rue Saint-Pierre — the first opera house in North America, which opened in 1792 — was presenting full-length operas and comic works that had premiered in Paris only a few years earlier. Audiences crowded in to hear Pierre-Alexandre Monsigny’s Le déserteur and Le Roi et le fermier, or André Grétry’s Silvain and Le tableau parlant, while Spanish zarzuelas like El maestro de baile and Italian intermezzi also found their way to the stage. One early visitor marveled that “the theater is crowded with a public as brilliant as that of Paris; the ladies are richly dressed, the orchestra excellent, and the whole city seems transported with the charms of music.”

Sacred music flourished at St. Louis Cathedral, where the blend of French and Spanish Catholic traditions gave rise to elaborate Masses and motets. In the salons of wealthy Creole families, chamber music by Mozart, Corelli, and Haydn was played with the same ease as in European capitals. Music was not just an imported luxury — it was the lifeblood of civic culture.

Yet the most distinctive musical gatherings took place not in the salons or theaters, but in the open air of a field just outside the French Quarter: “Place des Nègres” — later called Congo Square. There, every Sunday, enslaved Africans were permitted to gather, a rare concession in a slave society. They danced, sang, and drummed in circles, playing instruments such as banjos, gourds, and drums that bore the imprint of West and Central African traditions.

The scene astonished visitors. The French traveler Moreau de Saint-Méry, writing in the 1790s, described how “two drums provide the beat, while a banza [banjo] plucks out a melody, and the women turn and spin with gestures that are sometimes lascivious, sometimes noble.” He added, almost in disbelief, that the rhythms were “so complicated and interlaced that the ear of a European can scarcely distinguish them.”

Two decades later, the architect Benjamin Latrobe witnessed the same spectacle and recorded that “the music consisted of a long, monotonous chant, sung in chorus by the women, accompanied by the beating of an instrument, a sort of drum, kept between the legs of one of the performers… The dancers formed a circle, each in turn stepping within it, moving with incredible rapidity.” Latrobe sketched what he saw, giving us one of the earliest visual records of African dance in America.

The city’s population was diverse, marked by differences in freedom, origin, and culture. Enslaved Africans carried their traditions into Congo Square but had little presence in formal concert halls. Free people of color, however — many of them Creoles of mixed French, Spanish, and African heritage — played an active role in New Orleans’ musical life. Some were educated in Europe, while others were taught locally. Their participation in theater orchestras and church choirs gave them a presence unknown in most American cities of the time.

Creoles of European descent dominated the salons and opera houses, cultivating tastes that mirrored those of Paris. Spanish influence, too, lingered, evident in dance forms and repertory. In New Orleans, unlike Charleston or Boston, the city’s music reflected not one cultural current but several, braided together into something distinctively its own.

For Thomas Jefferson — himself a violinist who had once played string quartets with family and friends at Monticello — the Louisiana Purchase was more than a geopolitical coup. It pulled into the United States a city whose musical life was arguably more advanced than Boston’s or Philadelphia’s at the time.

Benjamin Franklin, who had spent years in Paris’s salons as a diplomat, might have recognized the cultural resonance. He knew firsthand how French opera and chamber music animated social life in Europe.

Jefferson also understood enough to grasp that New Orleans was not just a river port — it was a cultural capital.

The Mississippi River promised commerce, but it also promised the circulation of culture, with New Orleans as its southern gateway. Music, like goods, would travel northward on the river.

By 1803 (the same year Beethoven began composing his Symphony No. 3, the “Eroica”), classical music in America was still largely the preserve of elites, concentrated in a few Atlantic coastal cities. But with New Orleans inside the Union, the balance began to shift. The United States had acquired not only fertile farmland and strategic ports, but also an opera house, cathedral choirs, salon ensembles, and an African-descended musical tradition thriving in Congo Square.

It was, in retrospect, one of Jefferson’s most unexpected legacies: in making the Louisiana Purchase, he brought into the American fold a musical capital unlike any other — a place where European classics and African rhythms already met on common ground. New Orleans would not only enrich the young republic’s cultural life, but, in time, give birth to music that the world would call distinctly American. ■

Read more by Mark Gresham.

.png)