Mark Gresham | 29 OCT 2025

As the African American spiritual moved into the 20th century, it entered a new phase of preservation and reinvention. The urgent work of recording, collecting, and publishing the songs fell to a generation who recognized that this distinctly American music risked being lost if it remained only in oral tradition. Among the most influential were James Weldon Johnson and his younger brother, John Rosamond Johnson, whose dual gifts for words and music helped cement the spiritual’s place in the nation’s cultural record.

James Weldon Johnson, already a poet, novelist, and civil rights leader, viewed the spiritual as the authentic folk expression of the Black experience in America. His brother, J. Rosamond Johnson—a classically trained composer and conductor—understood the music from within, blending performance and pedagogy. Together, they brought literary and musical craft to the task of collecting and interpreting these songs before they were lost to time.

Their landmark anthology, The Book of American Negro Spirituals (1925), followed by The Second Book of American Negro Spirituals (1926), was more than a songbook. The brothers framed the African American spiritual not as a relic of slavery but as a national art form, equal to the folk traditions of Europe. Their introductions and commentaries provided one of the first serious written analyses of the form—its rhythms, dialect, theological meanings, and historical contexts.

The Johnsons also modernized spirituals for contemporary performance, publishing arrangements that allowed classically trained singers to perform them in recitals and on concert stages. Their work helped codify a canon of African American spirituals—songs like “Roll, Jordan, Roll,” “Didn’t My Lord Deliver Daniel,” and “Ride On, King Jesus”—ensuring they could be both sung and studied. Through their scholarship, the Johnsons connected the cultural work of earlier figures like the Fisk Jubilee Singers and Harry T. Burleigh with the literary and musical Renaissance then emerging in Harlem. Their anthologies became standard references for educators and performers, bridging oral history and written tradition and shaping how America—and the world—would come to understand the spiritual as art, history, and enduring testimony.

Burleigh’s influence continued to resonate in the early 20th century, inspiring composers such as R. Nathaniel Dett and William Levi Dawson. Dett, who taught at Hampton Institute, fused classical structures with African American melodies in choral works like Listen to the Lambs (1914) and The Chariot Jubilee (1919). Dawson’s Negro Folk Symphony, premiered by Leopold Stokowski and the Philadelphia Orchestra in 1934, wove call-and-response patterns and spiritual themes into symphonic form, affirming the music’s power to carry a nation’s moral and emotional story.

By the 1930s, African American spirituals had become symbols of both faith and freedom. Singers such as Marian Anderson brought them to global prominence. Her 1939 Lincoln Memorial performance—where she sang Burleigh’s arrangement of “My Soul’s Been Anchored in the Lord”—transformed the music into an emblem of civil rights and human dignity.

Even as jazz, gospel, and blues emerged, the DNA of the spiritual remained embedded within them: the call-and-response, the rhythmic drive, the cry for deliverance. The songs that once rose from the cotton fields had become the seedbed of nearly every form of American popular and classical music to follow.

Today, ensembles like the Fisk Jubilee Singers continue to perform, as do collegiate choirs across the nation, preserving the tradition while allowing it to evolve. Contemporary composers such as Adolphus Hailstork, Rosephanye Powell, and Tyshawn Sorey draw from that wellspring, proving that the spiritual remains not a relic of the past, but a living force in America’s musical identity.

The spiritual’s journey—from hidden gatherings in the antebellum South to conservatory stages and symphony halls—mirrors the broader African American struggle for recognition and equality. It is a story of transformation: from bondage to freedom, from anonymity to artistry. The spiritual remains America’s truest folk voice—born in bondage, lifted in faith, and carried forward by generations who understood that freedom, like music, must always be sung into being. ■

Read Part 1 of this two-part feature on African American spirituals:

Read more by Mark Gresham.

RECENT POSTS

Atlanta Symphony celebrates Indian and Western classical fusion in “Celestial Illuminations” program • 29 Oct 2025

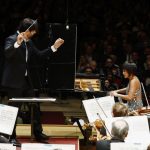

Atlanta Symphony celebrates Indian and Western classical fusion in “Celestial Illuminations” program • 29 Oct 2025 Domingo Hindoyan leads Boston Symphony in fearless Bernstein, Prokofiev, and Copland, pianist Yuja Wang solos with brilliance • 28 Oct 2025

Domingo Hindoyan leads Boston Symphony in fearless Bernstein, Prokofiev, and Copland, pianist Yuja Wang solos with brilliance • 28 Oct 2025 Conductor Arthur Fagen earns strong Italian press for Mozart’s ‘Don Giovanni’ in Jesi and Novara • 27 Oct 2025

Conductor Arthur Fagen earns strong Italian press for Mozart’s ‘Don Giovanni’ in Jesi and Novara • 27 Oct 2025

.png)