October 28, 2025

St. Luke’s Episcopal Church

Atlanta, Georgia – USA

Choo Choo Hu, piano; Emily Koh, double bass; Robert Anemone, violin; Laura Usiskin, cello; Elizabeth Labovitz, dance; David West, dance.

Caroline SHAW: Gustave Le Gray (2012)

Majid ARIAM: Life Cycle ex.3 (2020)

Jessie MONTGOMERY: Rhapsody No. 1 (2014)

Michael KURTH: The Monster Never Tires! (2014)

Kaija SAARIAHO: Im Traume (1980)

Edna LONGORIA: Inspiración Huasteca (2019)

Howard Wershil | 31 OCT 2025

It’s not an unusual occurrence for a new music ensemble to schedule a lighter, less stylistically intense program than usual for its listening audience, especially if that program responds to an event of collective interest. In the case of this evening’s wonderfully entertaining and enlightening concert at the spacious, awe-inspiring St. Luke’s Episcopal Church, ensemble vim, with its own brand of style and panache, has accomplished this to marvelous advantage. The evening’s theme of “Mystery & Transformation,” perhaps gingerly aligned with Halloween, presents audiences, both new and old, with just the right amount of intrigue to sonically celebrate this spooky occasion.

The first piece on this concert, Caroline Shaw’s Gustave Le Gray (2012), proved to be a quite charming and alluring piano composition inspired by, and quoting parts of, Chopin’s Mazurka in A Minor, Op. 17 No. 4. The composition begins with sweet repetition, using, as Ms. Shaw points out in her program notes, “chords and sequences presented in their raw, naked, preciously unadorned state—vividly fresh and new, yet utterly familiar.” As the piece progresses, the repetition persists, but scant dissonances are thrown in, and the mood shifts from familiarity to mystery.

The pace of the piece and its harmonies somehow reminded me of Chopin’s Prelude in E minor, Op. 28 No. 4, which, at that point, I fully expected the piece to quote. Having not yet read the program notes, I was surprised and delighted to hear the particular Chopin quotation used by Caroline Shaw emerge from the preparatory clouds of sound and express its full grandeur. Interestingly, both my expectation and her selection share a certain kinship in their use of harmonic progression to hold your attention by defying resolution at certain points. The piece exits from the quote by identifying shorter phrases to employ, again applying repetition to these phrases, before the music ultimately fades into the ether.

Pianist Choo Choo Hu gave us a sensitive, grounded performance of the piece. My attention was especially drawn to her rendition of the Chopin quote itself. Although I found it somewhat stylistically different than other interpretations I’ve heard (and note that, being a number of decades old, I’ve listened to a few), I found hers to be more natural, more flowing than older interpretations, as if, for her generation, this piece was already an old, integrated friend to her repertoire and history. Perhaps the lesson here is that, from our perspective, as the music grows older and the performers grow younger, the musical renditions are revitalized, providing us with more warmth, depth, and comfort. My sincere compliments to the musician, whose performance confidence seemed second-nature, just a breezy afterthought born of keen training and extreme talent.

The piece was accompanied by a sparkling dance performance by Elizabeth Labovitz and David West, members of dance company Wabi Sabi Terminus. Their flow through space, endearing looks, heartfelt courtship, and ultimate grace were a well-deserved companion to this attractive composition.

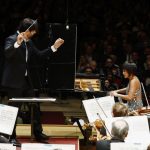

Pianist Choo Choo Hu and dancers Elizabeth Labovitz and David West perform Caroline Shaw’s “Gustave Le Gray.” (credit: Michael Hull)

Our next piece of the evening, Majid Ariam’s Life Cycle ex.3 (2020), provided us with a stark stylistic contrast to the previous composition. Majid is a prolific Atlanta-based composer well-known in new music and improvisational performance circles. He has performed extensively throughout Europe and the United States, and has received a notable number of awards and mentions for his creative efforts.

Using both technology and theatre, Ariam expresses his aesthetics with (per his program notes) “focuses on resonance and dynamics, experimental approaches, and [an orientation towards] the natural world, and reimaginings thereof.”

Double bass performer Emily Koh introduced Life Cycle ex.3 as a musical experience expressing how repetition makes us think about tiny things… and tiny changes. We are greeted (if you will) with a prepared double bass, with patches of clear plastic tape affixed to the instrument at various points. The piece begins with a 4-times alternation of the performer tapping strings with the wooden part of the bow (in an asymmetric pattern) and audibly breathing solo. This is followed by purposefully screechy bowing on the strings, also organized in a repetitive pattern. As the piece unfolds, we’re presented with other patterns, made from materials born of both a conventional and highly altered stringed instrument.

Ariam’s use of repetition is purposeful, useful, expressive, and even meditative. In fact, on many levels, the entire piece feels meditative, despite the occasional forays into louder, more strident materials. The attached tapes seem to allow for altered sounds that provide a more gutsy, visceral effect from the strings. Throughout the piece, change is slow, phrases vary widely in length, and descents into darker levels of sonority occur that are appropriately portentous in nature. At one point, detuning of strings with pegs as a sustained pitch is bowed provides another slow descent, this time into a muddy, anything-but-string-like declaration of natural truth. Somehow, emerging from this earthiness, the tone of the piece changes, with a return of the bow’s wood tapping on strings. Yet somehow, this return seems different—almost triumphant, even canonical. The tapping speeds up, then slows, leading to a continuous ruffling of plastic, then more wood pounding on strings, then bowing of the plastic, getting slower, slower, slower, leading to a gentle and calming conclusion.

Most of the sounds used in this piece were very guttural and conventionally considered non-musical in nature, but somehow subjugated and subdued by the composer to make a most divine musical expression! As a composer and an aficionado of experimental music, I know how challenging it is to work with unusual materials and non-conventional forms. What was so marvelous about this piece was that its dramatic elements were organized in such a way as to give it a palpable logic, a clear direction, and an expressive sensibility—not an easy task for any composer. Majid Ariam achieves this goal far more convincingly than many other so-called “experimental” composers, and for this we should be grateful. I must commend Emily Koh for her extremely attentive performance of this unique piece, not only for her adventurousness but also for the sensitivity necessary to communicate the goals of such experimental endeavors successfully. I very much look forward to seeing what she provides us next.

Our third piece of the program was Grammy Award-winning composer Jessie Montgomery’s Rhapsody No. 1 (2014), performed exquisitely by violinist Robert Anemone. The first of six solo violin pieces, each drawing its inspiration from a historical composer and intended to honor a contemporary violinist, this piece was composed by Ms. Montgomery for herself to perform, and she chose to base it on the solo violin works of composer and master violinist Eugène Ysaÿe (1858 – 1931). Not being familiar with Ysaÿe’s work at the time of the performance, I appreciated the opportunity to experience the piece without such referential knowledge.

The piece begins very much like any familiarly virtuosic solo violin presentation, but proceeds to interject momentary excursions to contrasting harmonic realms, ultimately providing a personalized blend of styles with enough dissonances and departures from the norm to render the language truly contemporary in nature. Montgomery’s compositional approach here certainly elicits a satisfying amount of drama, pulling back, then forging forth, with sensuality, melancholy, aspiration, and tenderness. I was left with the impression of having just heard a very beautiful free-standing musical homage, genuine, heartfelt, and deserving in its own right.

As seemingly intended by the concert’s unfolding form, Rhapsody No. 1 again provided a contrast with the prior performance by offering us more familiar stylistic ground on which to tread. Michael Kurth’s The Monster Never Tires! (2014) builds upon that brief excursion into familiar territory with a rousing piece, almost cinematically Western-genre-sounding in nature, and with an equally rousing, energetic performance by master cellist Laura Usiskin. It was perhaps the most accessible piece of the concert, with a relatively simple form, musical elements we can all resonate with, and predictable satisfaction.

In celebration of its contemporary take on relatability, the piece does play with repetition, interjections, phrase lengths, and consonance versus dissonance—and lots of downward dual cello string slides, just to liven up the already-whirling palate. All that said, it would be remiss of me to fail to provide composer Kurth’s own enigmatic program notes, which stand at such stark contrast to all I’ve just claimed:

Our next piece, Im Traume (1980) by Kaija Saariaho, returns us to the more vivid and dramatic elements of contemporary music, providing a quite mysterious and dramatic portrayal of the chaos encountered in the experience of dreaming. Such a complex piece of music would present an extreme performance challenge for any performers, but pianist Choo Choo Hu and cellist Laura Usiskin met the challenge brilliantly, imbuing the piece with extraordinary energy and transparency.

As opposed to the other pieces on the program, there’s no structural repetition here! This was probably the most contemporary-sounding (or perhaps late 20th-century-sounding?) composition on the program, showcasing a wide range of sonic materials and a wide variety of available sonorities from both the piano and the cello. At various points in the piece, upward and downward sweeps of sound from both the cello and the piano increase our sense of mystery and foreboding, as does the use of strummed strings inside the piano, and the employment of occasional scratchy cello declarations. A unique surprise of the piece in the midst of its development is a long, low, solo sustained pitch from the cello—perhaps representing a suspension of belief?—that deftly leads back to more chaos and mystery. How can I describe the shape of this piece? Was it circular? Was it spiral? Did it celebrate the path of an insect in flight through purgatory? It can only be determined by your own experience of experiencing the experience itself… dream on!

Robert Anemone, Choo Choo Hu, and Laura Usiskin perform “Inspiración Huasteca” by Edna Longoria. (credit: Michael Hull)

The final piece on the program, Inspiración Huasteca (2019) by Edna Longoria, capped the event joyfully. The composition’s very traditional musical language was distinctly Hispanic-derived, reminding me somewhat of some works by Astor Piazzola and other contemporary composers of Hispanic descent. The music was composed for dance purposes and to help celebrate the Day of the Dead. While the piece employs some repetition, it definitely is not about repetition, but more expressive of fire, motion, festivity, and even occasionally of fear and anticipation. Its odd-lengthed phrases of conventional musicality could easily both defy and promote a dancer’s spirit and resolve. That spirit and resolve were reflected with extreme jubilation by violinist Bob Anemone, cellist Laura Usiskin, and pianist Choo Choo Hu.

’Tis now the season where trick-or-treaters show in full display the range, depth, and variety of their own expressive creativity. And so it is with the creativity of today’s composers and the multiplicity of musical genres within which they work. Tonight’s pleasing display was merely a taste of the feast; “Mystery & Transformation” is simply one of a multitude of possible approaches to an exploration of this special sonic universe.

Should tonight’s new music be all that an ensemble can offer to elicit the terrors that the season invokes, then there is, I assure you, nothing to fear from engaging in these sonic endeavors throughout the year.

But just in case I’m wrong: Boo!

Good Tidings To All! ■

EXTERNAL LINKS:

- ensemble vim: ensemblevim.org

- Wabi Sabi Terminus: terminusmbt.com/company/wabi-sabi

Read more by Howard Wershil.

RECENT POSTS

Atlanta Symphony celebrates Indian and Western classical fusion in “Celestial Illuminations” program • 29 Oct 2025

Atlanta Symphony celebrates Indian and Western classical fusion in “Celestial Illuminations” program • 29 Oct 2025 African American spirituals: preserving the heritage, from the Johnson Brothers to today • 29 Oct 2025

African American spirituals: preserving the heritage, from the Johnson Brothers to today • 29 Oct 2025

.png)